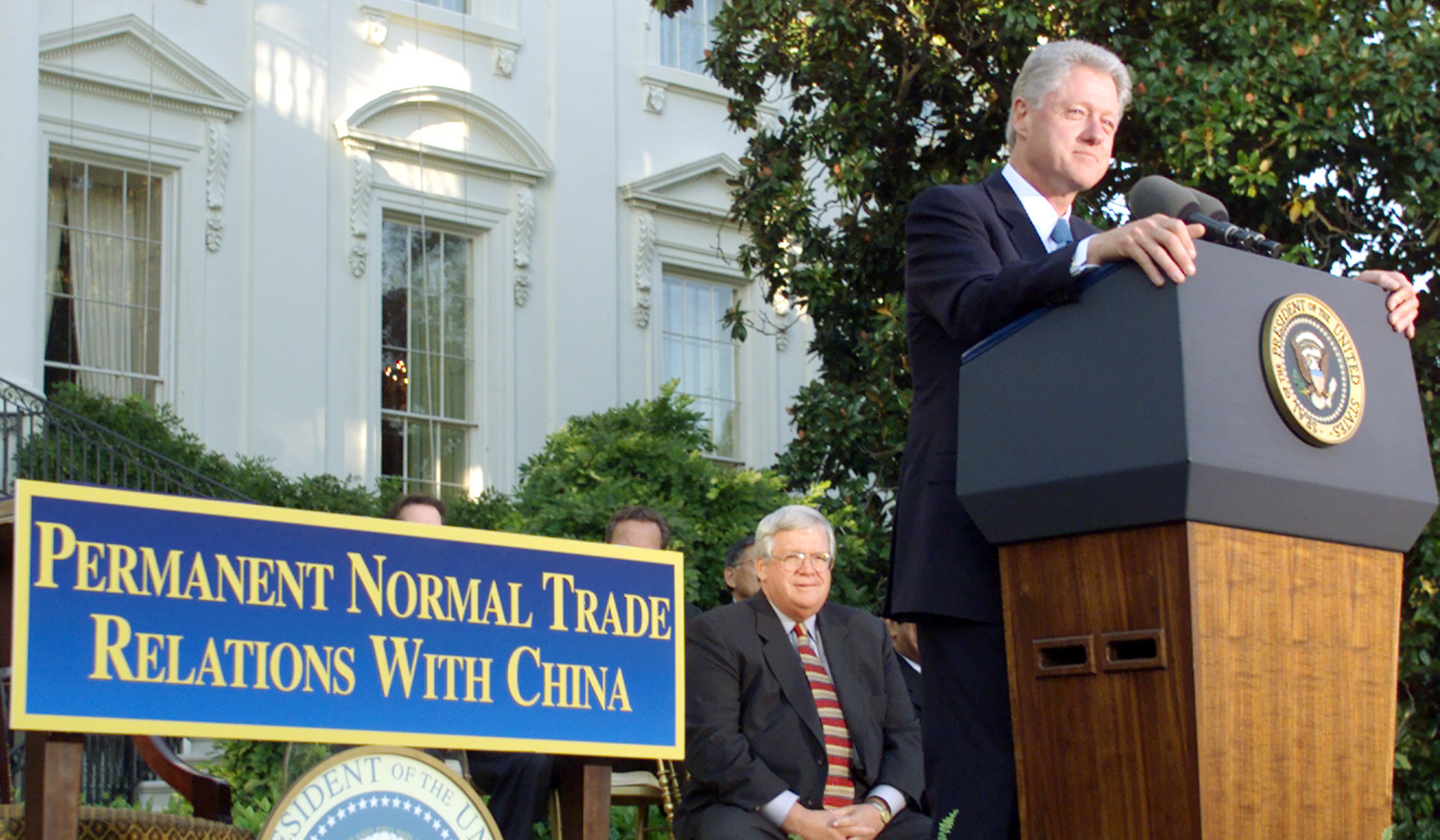

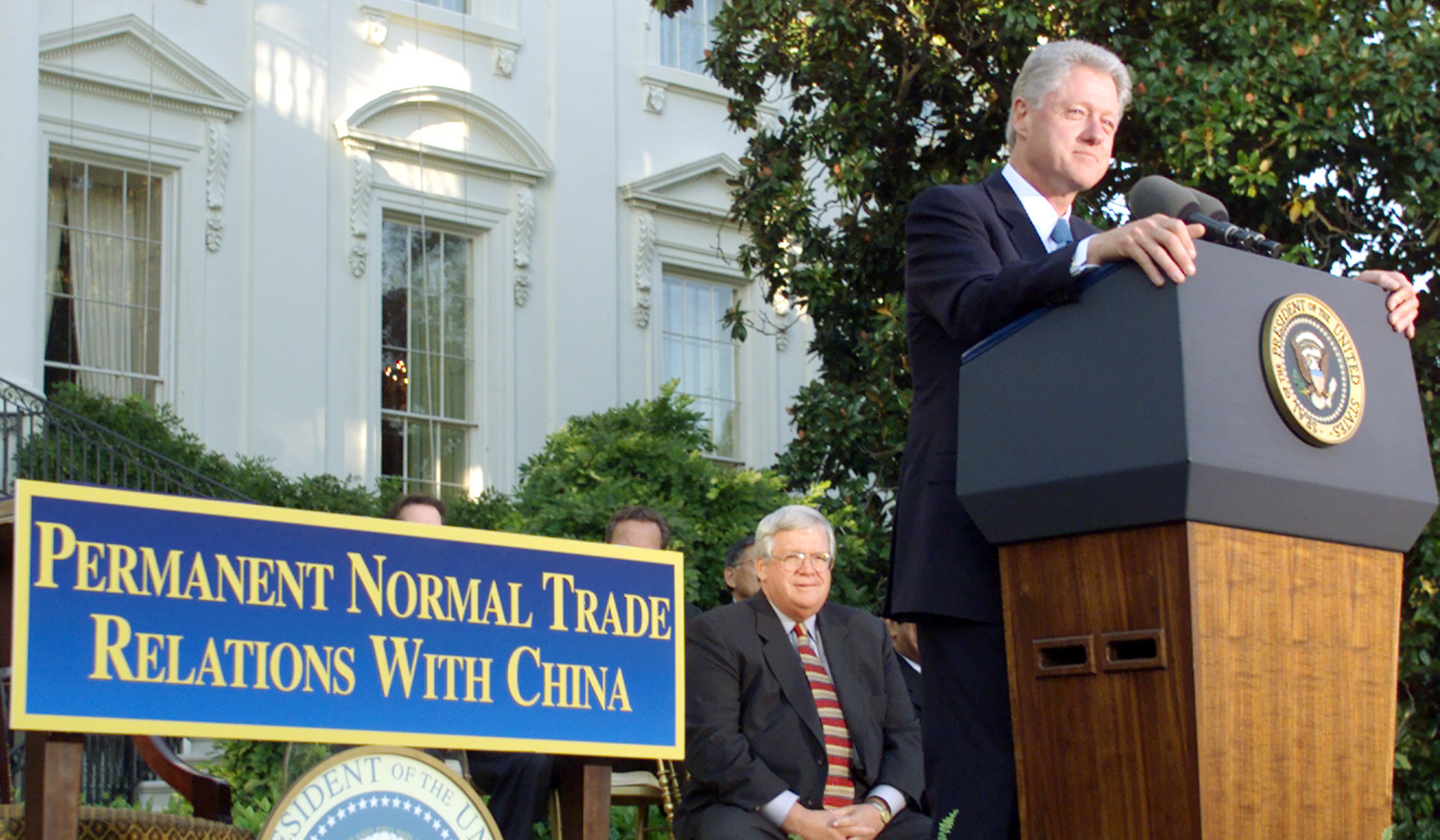

President Bill Clinton speaks about trade with China on the South Lawn of the White House in October 2000. (William Philpott/Reuters)

President Bill Clinton speaks about trade with China on the South Lawn of the White House in October 2000. (William Philpott/Reuters)  President Bill Clinton speaks about trade with China on the South Lawn of the White House in October 2000. (William Philpott/Reuters)

President Bill Clinton speaks about trade with China on the South Lawn of the White House in October 2000. (William Philpott/Reuters)

After World War II, the American foreign-policy establishment was caught up in an intense debate: “Who lost China?” Someone had to be blamed for Mao’s takeover. Today we are hearing the stirrings of a new debate: “Who lost China a second time?” China is marching toward global technological leadership and increasingly challenges the United States both economically and militarily in what Michael Lind has termed Cold War II. Who was responsible for letting this happen?

At one level, China lost China. As Michael Pillsbury writes in The Hundred-Year Marathon, China has had a strategy to supplant the United States as the dominant military and economic power since 1949. Now China seeks not just economic growth but technological leadership. President Xi Jinping himself has stated that China wants to be “master of its own technologies.” Indeed, China seeks not only mastery but global dominance in a wide array of advanced-technology products including artificial intelligence, computers, electric vehicles, jet airplanes, machine tools, pharmaceuticals, robots, and semiconductors.

It would be one thing if China did this through “fair” means, such as support for university research or a generous research-and-development tax credit. But as my organization, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), has documented, China has deployed a vast panoply of “innovation mercantilist” practices that seek to unfairly advantage Chinese producers. These include requiring foreign companies to transfer their technologies to Chinese firms in order to access the Chinese market; theft of foreign intellectual property; manipulation of technology standards; massive subsidies; and government-backed acquisitions of foreign enterprises.

But U.S. policy (or lack thereof) has both enabled China to run faster in that marathon and done little to slow it down.

As Pillsbury writes, “for more than forty years, the United States has played an indispensable role helping the Chinese government build a booming economy, develop its scientific and military capabilities, and take its place on the world stage, in the belief that China’s rise will bring us cooperation, diplomacy, and free trade.” Clearly that has not happened. But it’s worse, for China now seeks not just economic growth but technological leadership.

In addition, the U.S. has done virtually nothing to prevent China from deploying its mercantilist arsenal for almost three decades. The story begins with Richard Nixon, who, on the advice of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, opened the path to normalized relations with China in order to widen the emerging Sino–Soviet split. Nixon’s gambit created the political space in China for major economic reforms, which would prove crucial to Chinese economic growth and enable it to establish closer economic ties with the United States. Opening up was inevitable, but by doing it then, Nixon accelerated China’s rise by at least a decade.

Seven years later, Jimmy Carter, in an effort to normalize relations with China, signed a far-reaching science-and-technology cooperation agreement that over the last 40 years has helped China close its technology gap with the United States. This agreement led to tens of thousands of Chinese students’ enrolling in science and engineering programs at American universities, with much of the expense paid for by the United States, and to programs to transfer U.S. technology to China in areas such as energy, space, and commerce. The administration also established and paid for the development of the National Center for Industrial Science and Technology Management Development, in Dalian, to train future managers of Chinese state-owned companies in Western management practices. Michel Oksenberg, who was a senior staff member of Carter’s National Security Council, justified these efforts on the grounds that “over the long run, we are participating in the training of China’s future scientific community . . . and this should have profound and (on balance) favorable consequences for the United States.” In hindsight, he was partly right: This did have profound consequences, but by enabling direct competitors to U.S. advanced-industry firms, it had unfavorable consequences for the United States.

Next in line is Bill Clinton, who championed China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) and supported establishing Permanent Normal Trade Relations with China. The hope — and, in hindsight, naïveté — was enormous. Clinton called China’s accession “a hundred-to-nothing deal for America when it comes to the economic consequences,” arguing that the agreement “meets the high standards we set in all areas” and that “it is enforceable and will lock in and expand access to virtually all sectors of China’s economy.”

But, as the ITIF’s Stephen J. Ezell and I showed in a 2015 report, China failed to fully comply with most of its WTO-accession commitments and membership requirements. Indeed, China has skillfully used its WTO membership as blanket immunity from prosecution for its innovation-mercantilist policies. For example, Chinese officials know they would risk a WTO case if they put their forced-technology-transfer policies in writing, and so the policies are enforced informally but no less strictly. Yet the United States can no longer take unilateral action against China without triggering a WTO complaint and finding of violation of WTO rules (as we will likely see in response to President Trump’s recent decision to impose tariffs on Chinese goods).

Next up is George W. Bush. The Bush administration made it quite clear to U.S. firms, and to China, that moving jobs to China was not only acceptable but laudatory. Greg Mankiw, Bush’s top economic adviser, called the offshoring of jobs to China a “good thing.” Mankiw believed this because, according to conventional trade theory, all trade and foreign investment improve economic welfare. But since much of this offshoring was done because China was artificially suppressing the value of its currency (making its exports cheaper) and requiring U.S. companies to invest there to gain market access, at least some of the U.S. offshoring was not part of the working of the global free market, but reflected mercantilist distortions that harmed U.S. economic welfare. Bush’s Commerce Department actually hosted conferences for U.S. companies to help them figure out how to invest in China. The light was green for businesses wanting to move jobs and investment to the Middle Kingdom.

The Bush administration gave the same signal to China when it rejected petitions to put tariffs on Chinese-subsidized exports to the U.S. One provision in China’s WTO-accession agreement, Section 421, allowed the U.S. to levy tariffs to limit harm to U.S. industry from Chinese import surges. When the Bush administration rejected a 421 product safeguard in its first term, it sent a very clear message to the Chinese that the U.S. would not risk disrupting the economic and political relationship between the two countries over unfair trade practices. Beijing understood that it could continue export-dumping and other unfair practices with impunity.

In Bush’s second term, Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson established the Strategic Economic Dialogue with China, a formal process by which officials could discuss topics related to economic relations between the two nations. This was done not to force China to roll back its mercantilist practices but to defuse tensions at home, where many in Congress wanted China labeled a currency manipulator for pegging the yuan to the dollar. When the Treasury secretary says that we “need China to get ahead of [China’s] growing economic challenges, which now threaten to interrupt its truly remarkable record of economic success in recent decades,” and that “we want China to become more of a technology innovator,” it’s clear this is a not an official who will confront China.

When Barack Obama was running for president in 2008, it appeared that things would change upon his election. Obama promised action on Chinese currency manipulation. He promised to bring many more Section 421 cases. He promised to ban toy imports from China and to open up Chinese markets fully to American goods. But once in office, he brought just one 421 case (on tires) and did next to nothing else to change the course of Chinese economic and trade policy. In fact, it was during the eight years of the Obama administration that China radically shifted its economic strategy: No longer happy being the global assembly line, it aimed to become the global advanced-industry powerhouse. Perhaps the Chinese government was on to something when it stated, the day after the election, that it was “elated” Obama had beaten McCain.

Indeed, Chinese leaders realized early on that while Obama might talk loudly on China, he carried at best a very small stick. A signal moment came during Obama’s first official trip to Beijing, in November 2009, when he downplayed the United States’ economic and political grievances and instead stressed how important it was for China to help America fight climate change, emphasizing that he was looking forward to deepening the partnership “in this critical area.” But this wasn’t all: Obama actually agreed to increase cooperation on civil aviation (e.g., to help the Chinese compete with Boeing); to conduct joint research on biotech innovation (to help the Chinese compete with our life-sciences industry); and to cooperate with China in other technology areas (even though China lagged the U.S. on virtually every technology at the time). The administration believed — wrongly, as it turned out — that if it cooperated in these technology areas, somehow the Chinese government would be more willing to respond to U.S. concerns over unfair Chinese trade practices. Obama even stated that the two nations should “respect each other’s choice of a development model” (even though the Chinese model was and is mercantilist). Chinese leaders must have thought they had died and gone to heaven. It was at this point that they knew they could take advantage of this president. And so they did.

As the years went on, the principal way the Chinese were able to avoid any real challenge to their agenda was to dangle the promise of “dialogue.” Indeed, the Obama administration was proud that it had expanded the dialogue established by the Bush administration into the Strategic and Economic Dialogue (which now formally included “strategic” matters related to issues such as North Korean nuclear weapons). But the Chinese government used the S&ED to implement its rope-a-dope strategy of obfuscation and delay. Each S&ED proclamation just kicked the can down the road, containing largely meaningless “commitments” by the Chinese government, which it generally proceeded to ignore with little consequence. For example, in the 2010 and 2012 S&ED meetings, China “reaffirmed its commitment that technology transfer is to be decided by firms independently and not to be used by the Chinese government as a pre-condition for market access,” a commitment the country continues to ignore.

Why didn’t the Obama administration do more? As noted, one reason was that the administration put saving the planet’s climate ahead of defending the American economy. A second was that administration officials sincerely believed that, through dialogue and experience, the Chinese government would see the light and finally embrace the one true path: the Washington Consensus model of development, with its pillars of free trade, light-touch regulation, financial liberalization, and low or zero tariffs.

However, these administrations didn’t act alone. They were cheered on by the stifling groupthink of the Washington trade and economics establishment, which, almost without exception, refused even to consider the possibility that Chinese economic and trade policies might pose a threat to the United States. The Washington elite-consensus view was and is that trade is always good (even one-sided free trade in which the other side is mercantilist); that while trade might hurt individual workers, it can’t hurt the overall economy; and that there is no difference between challenging foreign mercantilism and naked protectionism.

Coupled with this rigid adherence to a strict free-trade ideology came the argument that China simply could not succeed with a state-run economy. Wasn’t it obvious? The Chinese leadership had clearly never bothered to read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations.

With the election of President Trump and plainer signs of what is going on in China, it has become fashionable to engage in revisionist history. We did the best we could. We couldn’t have known. We made a bet and it didn’t pay off. Even recent converts who are now critical of past U.S. naïveté toward China still don’t seem to understand. One case in point is a recent article in Foreign Affairs, by former Obama-administration officials Kurt M. Campbell and Ely Ratner, called “The China Reckoning.” They counsel that the U.S. government should just stop trying to change China, “instead focus[ing] more on its own power and behavior, and the power and behavior of its allies and partners.” So, keep letting them steal, cajole, or coerce away our valuable technology. Keep letting them bestow massive market-distorting subsidies on their advanced-industry firms, taking market share from U.S. firms. Keep letting them limit exports from U.S. firms and deny our firms fair access to their markets.

That brings us to today. China is feeling its oats and understands that it can now be much more assertive, both militarily and economically. President Trump, to his credit, is the first U.S. president to forcefully confront China over its unfair economic practices. But when all is said and done, it is anything but clear that the Trump administration will succeed in rolling back these egregious practices. Indeed, the administration has made two strategic mistakes.

First, it has not appreciated that the odds of winning this “war” against China and having it roll back its mercantilist policies are extremely low without the support and commitment of our allies. As one top-level Chinese official told me, “We don’t fear the G-2 [U.S. and China] or the G-20; we fear the G-3, where the U.S. and Europe join forces against us.” But by levying steel and aluminum tariffs on our allies, threatening automobile tariffs on Japan and Europe, and recently isolating the United States at the G-7 ministerial meeting, Trump has thrown away any opportunity for an alliance of the willing. Indeed, the administration seems to believe that it is possible to fight a multi-front trade war and prevail. Moreover, when you have a president who believes, or at least says publicly, that “the EU is worse than China on trade,” you have a president who is not focused on the real problem. In terms of mercantilism, there is no question that China is an order of magnitude worse.

And second, even if unilateral action could in theory be effective, which is doubtful given that the Chinese authoritarian state can take much more pain from a trade war than can America’s democratic system, the seeming lack of consensus in the Trump administration would still make success unlikely. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin seeks a resolution to the conflict with China at almost any cost; Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross and the president are focused on reducing the trade deficit; U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer appears to be more concerned with rolling back unfair practices stemming from the “Made in China 2025” initiative:?This sends a message to the Chinese that the administration can’t agree on what it wants. More troubling is the fact that the administration appears to be considering a deal whereby we stop pressuring China if it reduces our trade deficit with it by buying more soybeans and natural gas. Such a deal would actually be in China’s interest, as it would reduce upward pressure on the yuan, making Chinese advanced-industry exports cheaper.

The U.S. government should have one and only one major trade-policy goal at this moment: rolling back China’s innovation-mercantilist agenda, which threatens our national and economic security. Only this can enable the United States to stay ahead of China militarily, technologically, and economically, at least for the next several decades. Unfortunately, after decades of capitulation and failure, success does not look much more likely today.

So who lost China this time? Pretty much everyone.