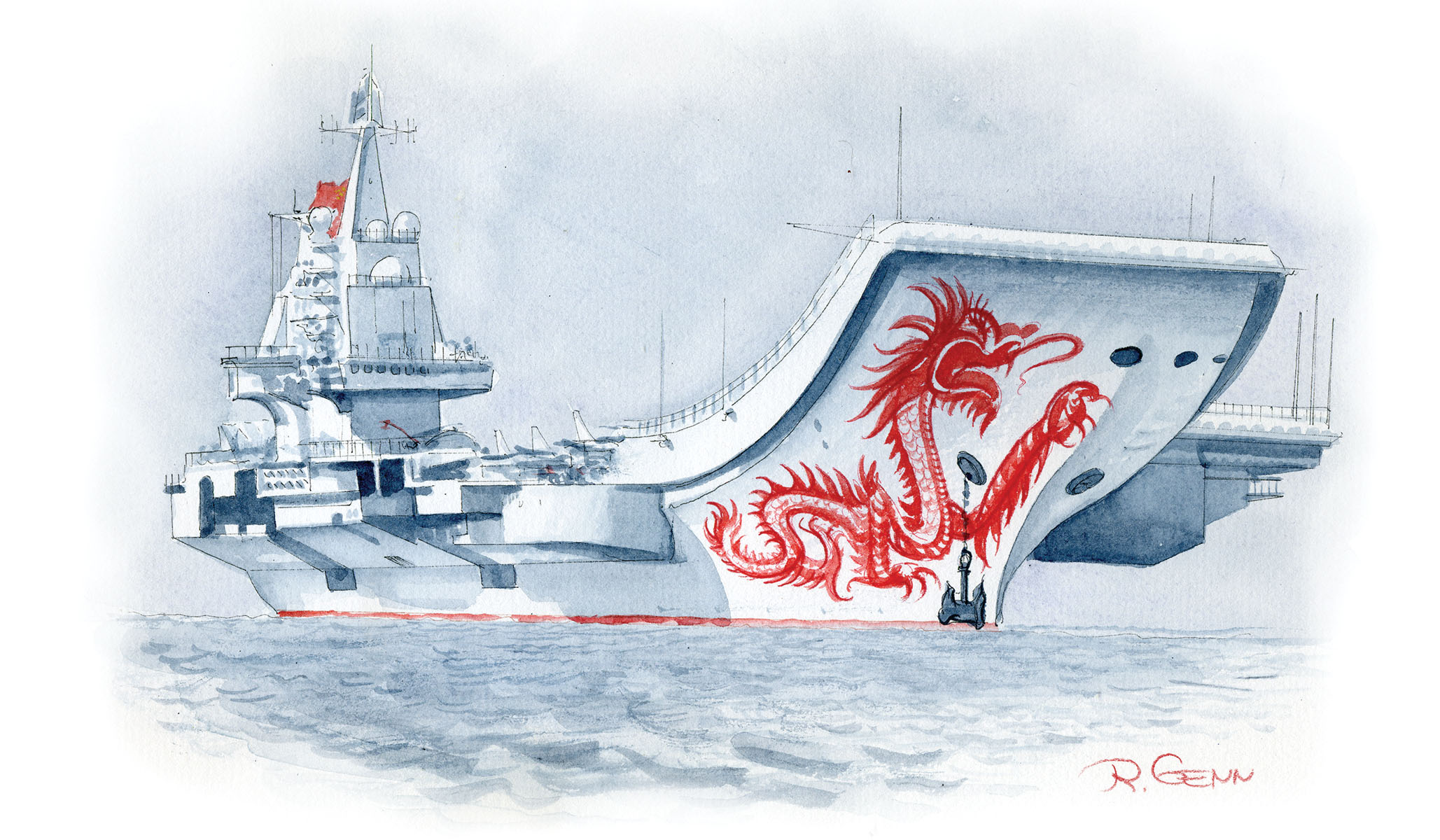

(Roman Genn)

(Roman Genn)  (Roman Genn)

(Roman Genn)

China is building a navy, and it clearly intends to challenge the United States and the broader international community — not only in the waters off its coast, but on all the high seas across the globe.

Of course, this is not a new insight. Defense leaders, including the late senator John McCain, have been highlighting China’s investments in new ships, including aircraft carriers and nuclear-powered fast-attack submarines, as well as advanced anti-access/area-denial weapons to thwart U.S. carrier groups. What is not understood is how two parallel policies over the past generation — one that guided the contraction of the overall size of the U.S. Navy, and a second that emphasized high-end capabilities in the ships that remained — effectively invited China and other nations to enter into a naval arms race with the United States. Also misunderstood is how critical it is to quickly answer President Trump’s call for a 355-ship Navy if we are to avoid a disastrous war.

Everyone seems to remember Ronald Reagan’s 600-ship Navy from the 1980s, but few understand how precipitate the decline was following the demise of the Soviet Union. First the Bush/Clinton “peace dividend,” and then the nation’s focus on its wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, saw the Navy fall from 592 ships in 1989, to 350 in 1998, to its nadir of 271 in 2015. While this was playing out, both civilian and uniformed leaders made the argument that the Navy did not require large numbers of ships so long as the ships it retained were of the most advanced designs. This answer appeared valid, in theory, but the reality was that a smaller fleet simply could not be everywhere we needed it to be at once.

The result has been a slow unraveling of the maritime order of free trade and free navigation that the United States and its Navy struggled so hard to build over the previous 70 years. The current situation recalls the “broken windows” theory of law enforcement first advanced by George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson in the early 1980s. The theory took its name from the phenomenon wherein an unrepaired broken window acts as a psychological invitation to break other windows. Kelling and Wilson argued that police could control crime by maintaining a general sense of order in their communities, with cooperation from the communities themselves. This entailed patrolling on foot rather than by car — so that officers would be seen as part of the neighborhood — and by taking “quality of life” offenses seriously.

Between 2001 and 2016, when the Navy was shrinking rapidly, the United States’ strategic focus was firmly locked on its counterterrorism wars in the Middle East and Central Asia. Most of the Navy’s deploying ships were either moving towards those conflicts or returning home from them, leaving entire maritime “neighborhoods” unpatrolled — and windows started to break. Fishing rights were trampled upon, sovereign claims over broad swathes of the high seas were advanced, critical energy infrastructure on the bottom of the sea was threatened, and ultimately fortified artificial islands were built in an attempt to expand anti-access/area-denial weapons systems. Window after window shattered without an appropriate response. The community began to lose confidence in the old free-trade and free-navigation rules and norms that the U.S. had established. Over time, disorder began to increase all over the world, encouraged by Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran. As an ancillary effect, acts of independent piracy increased off of Africa, in the Arabian and Red Seas, and even in the central Pacific.

To be clear, Navy ships continued to cruise through these troubled regions from time to time with their high-end carrier strike groups or even with their Aegis Combat System–equipped cruisers and destroyers, but there simply were not enough of these ships to patrol often enough to uphold norms. Plus, the Navy had become separated by a chasm of technology from the neighborhoods it was patrolling — much as police officers who remain in patrol cars fail to connect on a personal level with neighbors on the street. Allied and partner navies around the world, largely fielding frigates and coastal patrol craft, began to feel overawed as they looked up from their ships’ bridges at Americans towering over them in terms of both size and technology.

The composition of the American Navy has added to this sense of separation in another way. During much of the Cold War, when the U.S. was knitting together the international community, the Navy maintained nearly 200 ships — frigates, flat-bottomed amphibious ships, and patrol craft — that could make port calls into the large number of small and shallow harbors around the world. But today’s Navy, equipped with larger ships that sit deeper in the water, has lost contact with numerous vital maritime communities. It is no longer looking people in the eye and hearing their problems; instead it cruises through on its way to somewhere else and occasionally rolls down the window to peer out from behind mirrored sunglasses. Such separation created a vacuum, and power, like nature, abhors a vacuum. Rival powers have begun to fill it.

Russia deploys an increasing number of ships to the eastern Mediterranean, ostensibly to support its ally in Syria but tangentially to plant seeds of doubt within the NATO alliance. It has also increased its naval presence in the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans and the Baltic and Black Seas. Putin does not have a large navy, but he employs what he has for optimal effect.

Iran has demonstrated a mastery of small-gunboat operations in the Arabian Gulf. Its boats, manned with crews drawn from the zealous Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, make high-speed passes around American Navy ships, and a few years ago, in the dwindling facile days of the Obama administration, they even seized two American riverine-boat crews in international waters.

China continues to build one warship every two months, ranging from new aircraft carriers to guided-missile frigates that can visit a broad range of ports in the region. Soon the Chinese navy will surpass the U.S. Navy in size, and it is approaching capabilities parity as well. It is also stepping up its challenges to the U.S. Navy, as evidenced by its recent near-collision with a U.S. destroyer in the South China Sea.

These state actors are challenging the United States on the high seas because they perceive in the U.S. Navy’s shrinking numbers an opportunity to surpass a superpower. In other words, they are challenging the U.S. because the U.S., with its small and unbalanced fleet, has invited them to do so.

Such challenges are not to be taken lightly. While the United States has at last realized that it is once again in a great-power competition, it has not come to grips with the fact that such competitions are inherently unstable and have almost inevitably led to large-scale war. Those who point to the Cold War as a period of dynamic yet ultimately peaceful tension overlook the fact that it was a symmetric competition between two great powers — whereas true multi-power competitions, with three, four, or even five actors, often experience shifting alliances and rising instability. The era leading up to World War I, with its multipolar alliance structure and underlying arms races, is only the most recent of a series of such unstable international structures.

However, it should not be thought that all is lost and war is inevitable. There is still time to get out of the cruiser and back to walking the beat.

The Navy has settled on the goal of a 355-ship fleet. It has also initiated a selection process to begin acquiring a new guided-missile frigate beginning in 2020. During the Cold War, the Navy operated around 100 of these small, versatile, multi-mission ships, but today it has none in its inventory. Presently the Navy wants to buy around 50 of them, but based on deployment patterns and historical models, it will require around 73 frigates as part of a 355-ship fleet. It should also look to purchase some small patrol boats or offshore patrol vessels to replace its rapidly aging Cyclone-class patrol vessels. Such vessels, robust but low in price, can serve as the “cop on the beat” peace-preserving force in the world’s troubled regions, such as the Taiwan Strait, where two U.S. Navy ships recently sailed to demonstrate that the U.S. considers the strait to be international waters and thus open to free passage.

These ships, frigates, and patrol vessels are similar to ships found in the navies of many of our nation’s allies and partners and will allow them to look us in the eye as we work together to reestablish local legal and strategic norms. Smaller and with shallower drafts, such vessels will also be able to access smaller ports and harbors, allowing the Navy to interact with local governments and populations, rebuilding good will and trust. They will also help raise the morale of the Navy itself through positive feedback from these port visits and interactions. And deploying these vessels will free up more expensive and technologically complex ships to focus on training for the high-end, war-winning missions that they are optimized to accomplish.

The time has come to take another look at the composition of the high-end force as well. For the past three generations, the Navy’s high end has been dominated by the carrier strike group and its air wing. All the ships in the strike group — the carrier, cruisers, and destroyers — are arrayed to allow the embarked air wing, made up of approximately 65 aircraft of various types, to launch, hit their targets, and return to recover and reload. But the enemy gets a vote, and after some 70 years of unopposed carrier operations, both the Chinese and the Russians have begun to invest in long-range missiles that target the carrier and force it out from their shores, beyond the range of its embarked aircraft. This is a problem that has two solutions.

The first is for the Navy to extend the range and reach of its air wing. It could do so by building a new aircraft, probably unmanned, that could have the range, approximately 1,500 to 2,000 miles, to hit targets from a safe standoff distance. (This is actually the reason carriers became so large after World War II: to be able to launch and recover larger aircraft that could fly long distances while carrying a meaningful amount of ordnance.) The second solution is to shift the Navy’s strike emphasis to the undersea environment, where it still has a significant strategic advantage. A new generation of submarines, each equipped with a large inventory of standoff strike missiles, could also provide the penetrating volume of fire to take down enemy air defenses and command-and-control nodes.

Such a balance of high-end, war-winning ships and low-end, peace-preserving ships (which would also serve well in wartime) would allow the Navy to rapidly grow to 355 ships in an affordable manner. This would be key to convincing rising powers that they will never be allowed to surpass American naval capabilities or capacity. It would also enable the Navy to begin patrolling challenged areas, bringing pressure to bear against rising powers, reestablishing local norms, and encouraging American allies and partners to begin repairing the broken windows in their neighborhoods. Creating a new generation of war-winning capabilities will also create a new awareness of risk in those who would make themselves enemies of the United States.

Kelling and Wilson stated nearly three decades ago that “failing to arrest those who demonstrate disruptive behavior establishes a pattern of behavior for others that becomes more disruptive . . . over time” — and New York City demonstrated in the 1990s, through its crackdown on minor offenses, that high-crime areas can become livable neighborhoods once again. China didn’t start down the road towards building up its navy and competing with the U.S. at sea until it perceived that the U.S. Navy had vacated its regular patrol areas; the U.S., that is, invited these disruptions. It is time to invest in a 355-ship Navy that has the right balance between high capabilities and cop-on-the-beat presence.