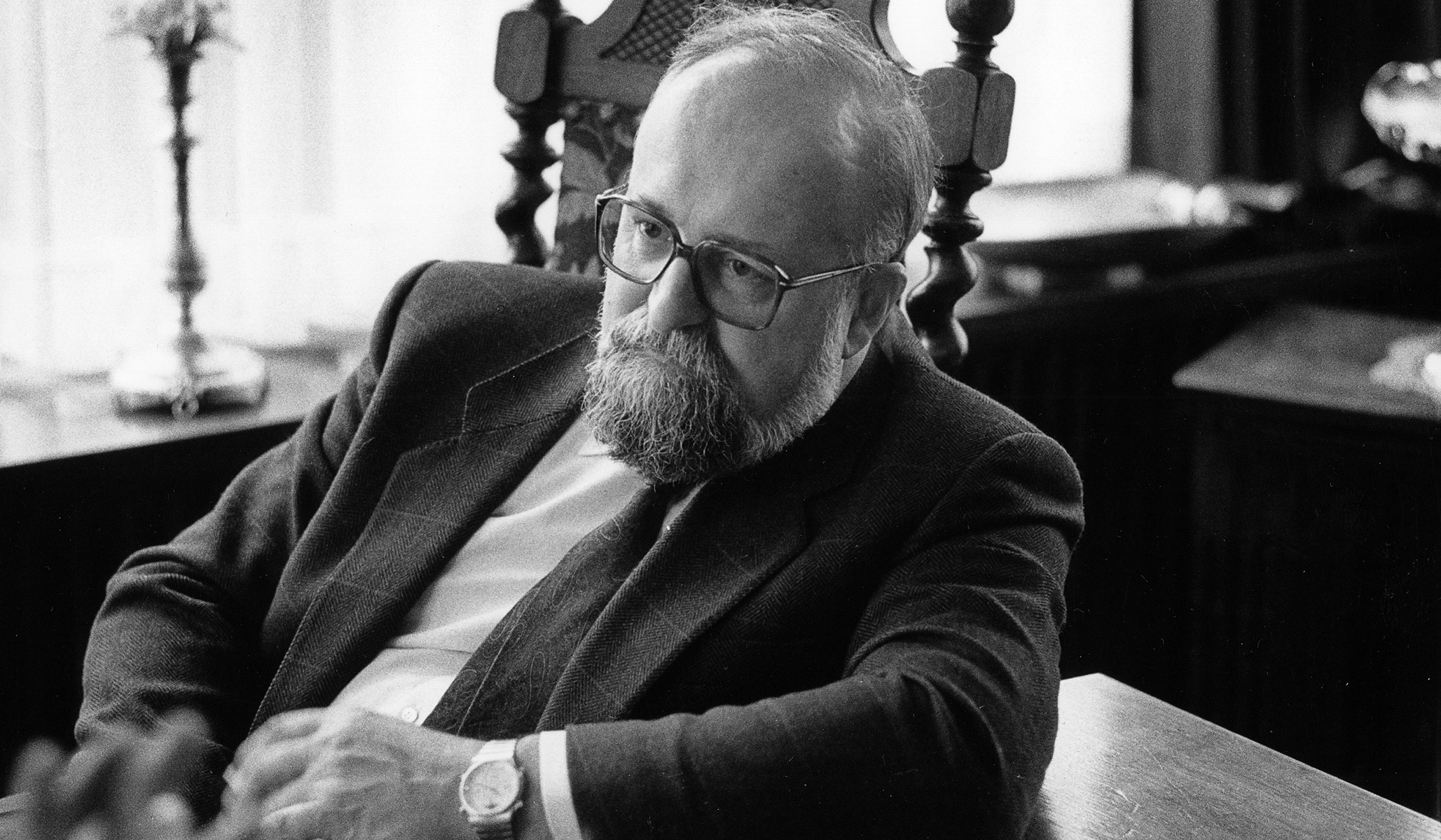

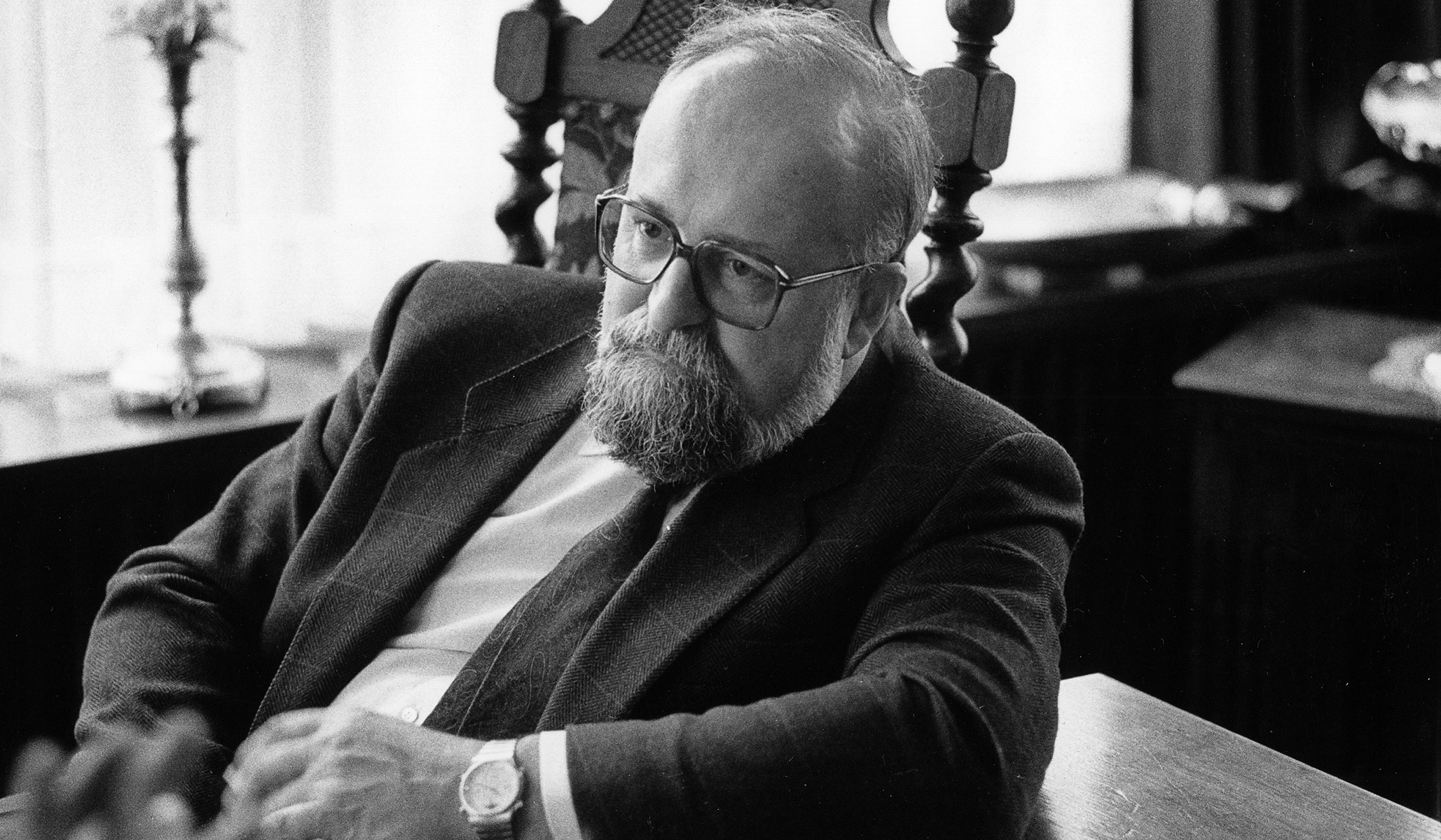

Krzysztof Penderecki, 1987 (Ullstein Bild/Getty Images)

Krzysztof Penderecki, 1987 (Ullstein Bild/Getty Images)  Krzysztof Penderecki, 1987 (Ullstein Bild/Getty Images)

Krzysztof Penderecki, 1987 (Ullstein Bild/Getty Images)

Over the years, I have interviewed many musicians, most of them performers, with a few composers sprinkled in. (On rare occasions, the interviewee is both: both performer and composer. “He rolls his own,” I often say of such a person.) One of my usual questions is, “Are there living composers you admire?” Lowering the bar, I might say, “Are there composers today you consider worth hearing?”

A composer friend of mine hates it when I ask this question, understandably. Yet a great many people ignore contemporary music, leaving it undiscussed. At least I’m not guilty of that.

I have received various answers about living composers. Some people say, “Oh, yes, my goodness, I could list them all day.” Some people — most people — offer a short, select list.

On one memorable occasion, I was doing a podcast with a famous pianist, and when I asked him about living composers, he looked at me with panic in his eyes. He mouthed something like, “I have no idea what to say.” I moved quickly on.

For all these years, musicians have tended to name one composer, above all — one composer who stands tall and stands out: Krzysztof Penderecki, of Poland. Indeed, when I asked the late conductor Lorin Maazel about composers — and he was one himself — he said, immediately, “Penderecki.” Then he paused a long while before adding a few more names.

Penderecki died earlier this year — March 29 — at age 86. Was he, is he, great? William F. Buckley Jr. liked to quote Stravinsky to the effect that you can’t tell about a composer until 50 years after his death. This is a commendable idea, but not necessarily true. Simply to pluck a name from the 20th century, it was obvious, virtually from the beginning, that Shostakovich was great.

And how about the composer of The Firebird, etc. (Stravinsky)?

Shostakovich died in 1975 (Stravinsky in ’71). Is he the last great composer? Not the last great composer who will ever live, but our most recent great composer? Is Benjamin Britten, who died in 1976? Whether or not Krzysztof Penderecki is great, he is formidable, without doubt.

Penderecki was born on November 23, 1933. He grew up in Debica, a town in southeastern Poland. His father, Tadeusz, was a lawyer who also played the violin and the piano. Tadeusz was descended from German Protestants; one of Krzysztof’s grandmothers was Armenian. “I’m quite a mix,” he once said.

Debica was about half Jewish. The Pendereckis — who were not Jewish — lived on the border of the ghetto. Krzysztof learned to speak a little Yiddish. Those neighbors would soon disappear.

Krzysztof was five when the war came — when the Nazis invaded on September 1, 1939 (and the Soviets 16 days later). Some of his family members died in the war, including an uncle who was killed in the Katyn massacre.

The influence of the war — intensity, horror, darkness — can be heard in the music that Penderecki wrote for 70 or so years. He once quipped — though it was more than a quip — that if he had been born in New Zealand, his music would have turned out differently.

Originally, he wanted to be a violinist. I chatted with him about this once, after the premiere of La Follia (2013), a piece that Penderecki wrote for solo violin, which is to say, unaccompanied violin. That piece will be played by virtuosos for generations to come, I wager. In any case, Penderecki, as a young man, turned wholeheartedly to composition.

He had a thorough schooling in counterpoint and other old forms. Bach was a lodestar, and would ever hover in the background of Penderecki’s life. I think of Christian Gottlob Neefe, the music master in Bonn — who gave young Beethoven the two books of The Well-Tempered Clavier and said, essentially, “This is it.”

In March 1953, when Penderecki was just 19, something wonderful happened: Stalin died. The dictator’s passing widened artistic possibilities in the Soviet Union and its bloc.

Later in the ’50s, Penderecki heard electronic music, which fascinated and excited him. Going radical, he wanted new sounds, a new music. “All I’m interested in is liberating sound beyond all tradition,” he said. The young man was at the forefront of the avant-garde — having instruments, such as his violin, make sounds they had never been asked to make before, and even inventing a new system of notation.

Penderecki’s most famous piece from this period is for string orchestra — 52 strings, to be precise: Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima. It is an alarming, screaming, shocking piece. A lot of people took it politically, which is understandable. But Penderecki did not really mean it that way. In the late 1990s, he commented, “I don’t write political music. Political music is immediately obsolete.” The Threnody endures, he said, “because it is abstract music.”

It has been used in movies and TV shows, such as Children of Men and Twin Peaks. Plenty of music by Penderecki has been used in movies and TV shows — in The Exorcist, for example, and The Shining.

In the mid 1960s, he wrote his St. Luke Passion, which was a curious combination, as it remains: oratorio meets avant-garde. Penderecki would never cease to write sacred music, including hymns, Masses — even a Kaddish.

But he would not write in the same style. Like Picasso — and Stravinsky, for that matter — Penderecki went through a variety of artistic periods. He often said that he wanted to be like Picasso rather than Chagall. The latter was a great artist, he said, but “was painting almost the same way for 50 years.”

In due course, Penderecki turned his back on the avant-garde. It was spent, he said. It had become “more destructive than constructive.” He often explained, “I did not want to be my own epigone”: a weak imitator of himself, writing the Threnody over and over. He recaptured tradition, emphasizing form. “Respect your form,” he advised.

Through the decades, he wrote for himself, primarily. Then for his fellow musicians, who would perform his music. Then for an audience (receptive, appreciative). And people wanted his music, turning to him for the big commission, the big event.

He was asked to write a piece for the 25th anniversary of the United Nations. And the bicentennial of the United States. And the 3,000th — 3,000th! — anniversary of Jerusalem. And so on.

By the time he was finished, he had a great corpus of works, comprising four operas, eight symphonies, a dozen or so concertos, chamber music — the gamut. Penderecki also taught and lectured. He wrote essays. And he conducted (his own music). Bespectacled and bearded, he looked like an academic, and sometimes a prophet.

Generally speaking, his music has both brains and emotion. It is intense, anxious, ominous — sometimes horrifying. I myself am sometimes puzzled by Penderecki’s taste for the dark side.

Consider The Dream of Jacob, an orchestral piece from 1974 (commissioned by Prince Rainier of Monaco for his silver jubilee). It could be the score to a horror movie. Indeed, Stanley Kubrick borrowed it for The Shining. From Penderecki’s pen, Jacob’s marvelous dream — “in thee and in thy seed shall all the families of the earth be blessed” — sounds like a nightmare.

Whatever you or I may think, Penderecki had his own vision, all life through, and he was faithful to it, whatever it was at any given time. He never stopped writing. He wrote every day, “trying to find something inside me,” as he said. He would sometimes stare at the empty piece of paper, thinking he could never fill it, that he had sung all his songs. Yet he managed.

He had at least one other interest, namely trees — “my second profession,” he called it. At his country house in Poland, he had what he reckoned to be the largest arboretum in Eastern Europe: 17,000 species. “My grandfather taught me trees and the Latin names of trees when I was five or six. His father was a forester, so he knew them all.”

Back in 2002, I interviewed Ned Rorem, the American composer born in 1923. When I arrived at his apartment, he asked what the weather was like outside. I said it was gloomy. “Good,” he said, “I like it that way.”

He would go on to remark, “We are living in the only period in history in which music of the past is stressed at the expense of music of the present.” Intellectuals know about visual art, past and present, Rorem said. They know about literature, past and present. But if they know any music at all, it’s pop music. “I and my brothers and sisters are not part of their ken.”

And the general public? The public “has no notion of what it is we composers do. We’re a despised minority. Actually, we’re not even that, because we don’t even exist, and to be despised, you have to exist.”

That is gloomy for sure (though not necessarily wrong). Yet Krzysztof Penderecki has managed to break through, to a degree. One thing that may hinder his reputation, I think, is his name — and the inability of people outside Poland to pronounce it. Forget that first name, that “Christopher,” that daunting collection of consonants. How about the last one? It’s a little tricky: “Pender-ET-ski."