(Roberto Parada)

(Roberto Parada)  (Roberto Parada)

(Roberto Parada)

Of all the angles one could take to critique the present state of leadership in California, perhaps none is as simple and objective as the basic fact of exodus.

Fiscal considerations are subject to idiosyncratic catalysts that skew the data for periods of time (to either the positive or the negative). Unfunded pension liabilities speak to a future problem to result from present malfeasance, but they still allow people to conclude, “Well, maybe that works out better in the future than it sounds now.” (It won’t.) The widening economic divide is felt to be a problem only by those on the losing side of it. A lack of cultural cohesion is not just “not a problem” for many on the left, but an explicit aim. California is a mess economically, fiscally, socially, educationally, and culturally, but in each category there exist sufficient can-kicking options, or at least prima facie “spin” opportunities, to soften the realities of what is taking place in the Golden State. But there is one basic, objective reality that is impossible to spin away — people are leaving in droves.

I suppose that some states or pockets of the country in various periods, likely cyclical ones, could be susceptible to mass exodus. Weather conditions, quality of life, scenic options, pace, energy, educational opportunities, job-market dynamics — there are always reasons that could lead one to leave a certain place for another. But every one of those issues was a magnet to California decade upon decade — not a deterrent to coming or staying. Come spend a day with me in Newport Beach sometime and tell me that the weather is the reason people are leaving this state. You can rest assured that no part of California will receive a failing grade for its weather.

To leave a spot often branded as paradise for its warm, sunny, and consistent weather, there has to be a catalyst. Dreamers long flooded into California because of an entrepreneurial culture that was real and palpable. From Hollywood to Silicon Valley, from the Central Valley to San Diego, from downtown Los Angeles to the Inland Empire, whether in entertainment, technology, agriculture, sciences, big business, or small business, there was a dream associated with being in California. It was aspirational. It was a spot of infinite opportunity that also had the Pacific Ocean and 70-degree weather. It was no accident that California grew as it did, and no accident that such profoundly important businesses grew here, came here, were founded here, and flourished here.

But, alas, it has been no accident, either, that all of this has wrenchingly reversed. The weather and the dreams have not changed. But the tax rates, the regulations, and the cultural climate have. And over two decades marked by a highly conscious policy shift, the Left has helped to reverse the New Year’s Day dynamic of folks around the country watching the Rose Bowl on ABC, wondering why they are shoveling snow off their driveways when those lucky SOBs in Pasadena are bathing in sunshine with a view of the San Gabriel Mountains. It takes a lot of work to reverse a force like that, but the work was done, and that force has been reversed.

There is no one factor that has provoked the exodus. In fact, nearly every person I have ever talked to who has left the state was willing to swallow one of the major disadvantages of life there. Perhaps they didn’t like the heavy tax burden but were willing to bear it in exchange for the various advantages that life there gave them. The inexorable increase in cost of living was a bear but acceptable up to a point. The regulatory burdens were unwarranted but tolerable if one could just manage to do whatever it was one aspired to do.

No, what caused and continues to cause the exodus out of California is not tax burden, or regulation, or cost of living, or housing prices. Rather, it is the burden, and regulation, and cost of living, and housing prices, and more.

The 13.3 percent top tax rate for California’s highest earners is the highest state rate in the nation and is obnoxious. The state’s “middle class” tax rates are far and away the highest in the nation as well, also obnoxiously. One making $58,000 a year in California is in a marginal tax bracket (9.3 percent) nearly double that of someone in Arizona making over $500,000 a year (4.5 percent). When you look at the $116,000–$250,000 level that a middle-class, dual-income family would likely make in California, the 9.3 percent marginal tax rate is higher than almost every single marginal state rate in the country.

But there is no evidence that the declining appeal of staying in California is simply a tax protest. On top of being walloped by taxes, one takes fiscal hit after fiscal hit — property taxes that average $5,000 per year for a lower-end middle-class home with no frills and that can easily approach $10,000 per year for the most mundane of tract homes. Utilities, car registration, insurance, and education expenses are all in the top decile.

One is being asked to pay a lot more to live in California, and yet education results are abysmal, crime rates are unacceptable (the state has the 14th-worst rate of violent crimes per capita), the electricity grid is a debacle, and the job market has hollowed out. (The CEOs of great California companies have maintained homes in Menlo Park or Palos Verdes; recent factory or plant expansions of the companies have gone to Nevada, Arizona, and Texas.) The value of living in California has declined but the cost has not been correspondingly reduced; in fact, it has exponentially increased. A business cannot survive when it raises prices while simultaneously making a worse product. Neither can a state.

California made a choice to adopt a cost structure perfectly tailored to the needs of its public-employee unions. (The same could be said of Greece.) Policy-makers have made a conscious decision to make no effort whatsoever to diversify the state’s revenue base. The extreme revenues that highly specialized companies in Silicon Valley have earned bought legislators time as they came out of the great financial crisis. But the dysfunctional dependency on a technology tax base in the go-go 1990s and the subsequent dot-com bust taught Sacramento nothing. Today, the state depends on a revenue base narrower than ever before, even as debt levels, pension-funding needs, and infrastructure needs are at code red. One need not ignore the blessing of high capital-gain revenue when Big Tech flourishes, but to assume that the gravy train will continue is perilous.

For the leftist ideologues who have brought about the exodus, an unexpected turn of events is taking place. The Left underestimated the impact of the pre-pandemic outmigration. It was never good for the fiscal and cultural health of the state that so many, after weighing the pros and cons, voted with their feet. One can be forgiven, however, for thinking that the Left was not all that shaken up by 650,000 middle-class people per year realizing that, in Texas or Arizona, they could buy more house for less money, with a smaller tax burden and greater job prospects for their kids. The “don’t let the door hit you on the way out” mentality of so many lawmakers was hardly disguised, especially while another social-media company was making an IPO or a new venture-capital fund was ringing the cash register.

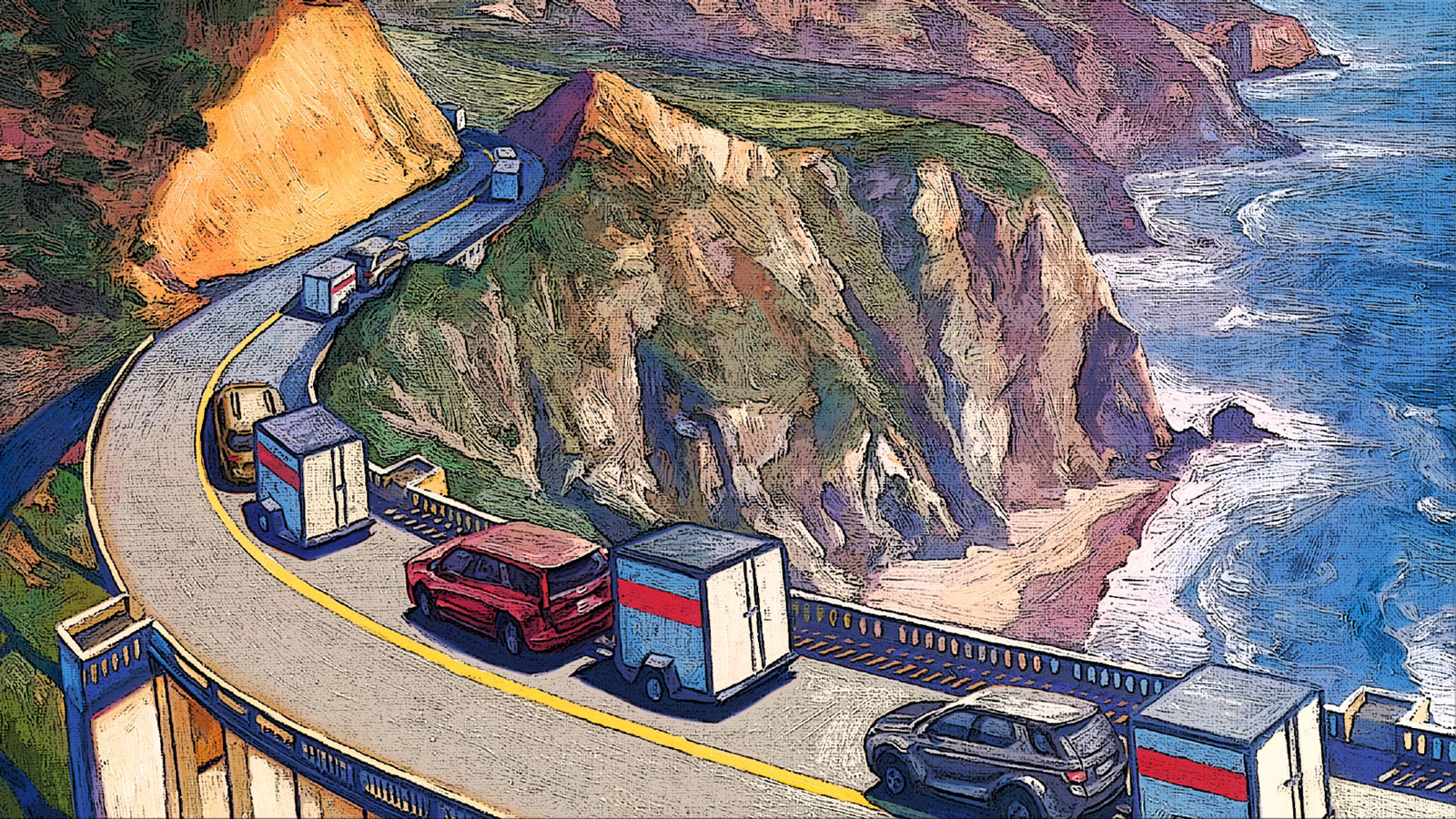

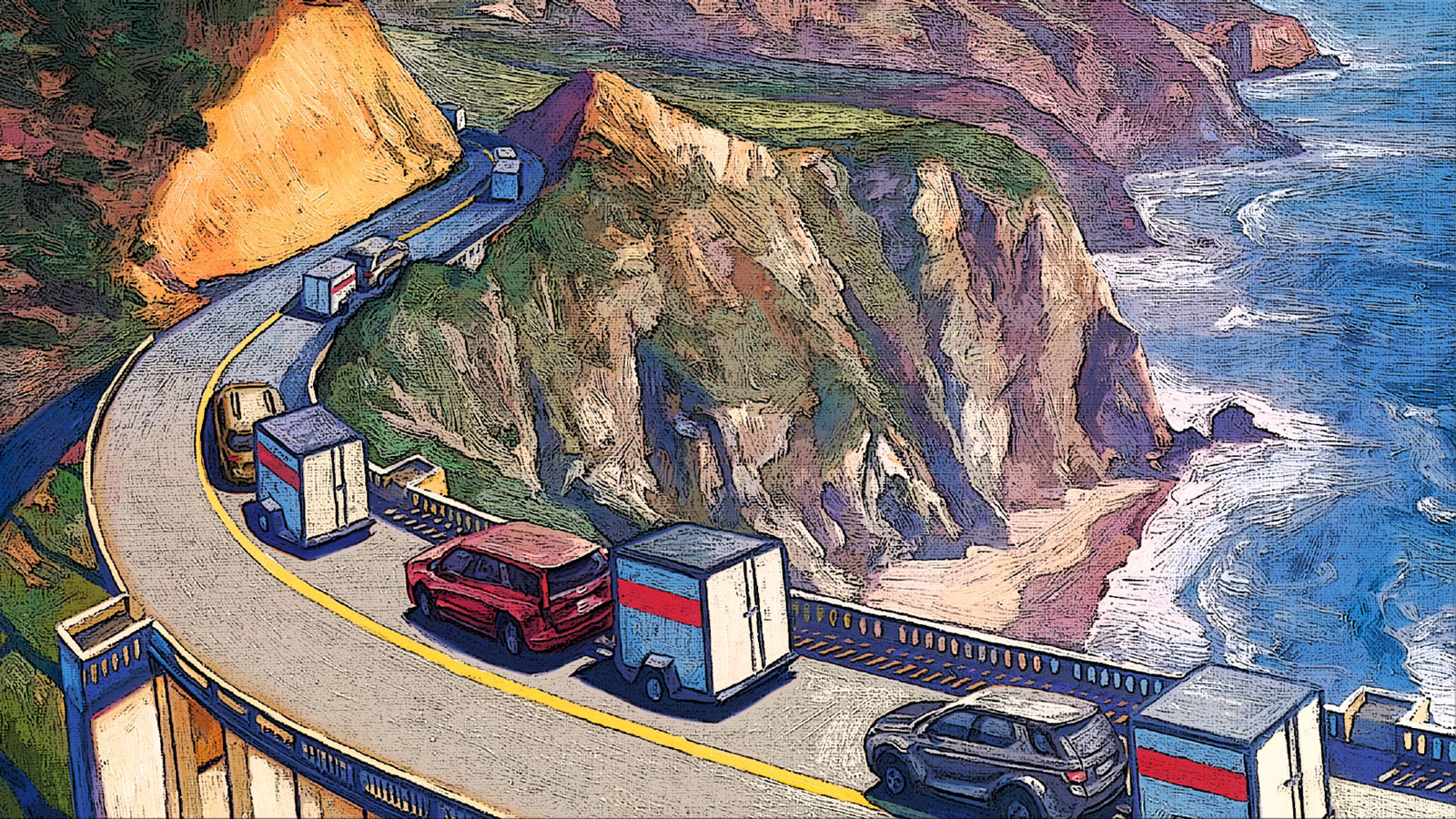

But the newest development in the Left’s fatal designs for this state is a game-changer. It is no longer just a family of four making $90,000 per year packing up the U-Haul and headed to Utah for a better life. The leftists themselves have had enough. The tech wizards of Palo Alto realize they have artisanal coffee shops in Denver, too. The cultural appeal of California has spread outside its own borders. Middle-class traditional families had already made the cost–benefit analysis of leaving the state, but now the gravy train has caught on as well. The Hewlett-Packards and the Teslas and select Silicon Valley gurus capture headlines now as they pack their own version of a U-Haul. What lies ahead for the state is ten years of a slow build of this same dynamic — even the cool kids are getting out of Dodge.

Legislators make conscious decisions sometimes. So do middle-class families. And guess what? So do hip, tech-savvy Millennials.